| Home Index/Indians | First Posted: Oct 27, 2009 Updated: Jan 21, 2020 | |

Native American (Indian) Symbols

Apache Indian Symbols

"Apaches were among the first Native Americans to ride horses into battle. In preparation, a warrior would decorate his horse to reflect his personal honors such as enemies killed or horses stolen. "A left hand drawn on the horse's right hip was one of the highest honors for a horse, earned by returning its rider from battle unharmed. Other symbols such as arrowheads and thunder stripes would augment the horse's natural ability and maximize its effectiveness against the enemy. The most sacred of all symbols in all Native American cultures is the circle, however, which for the Apache is most potently embodied in its chief symbol, the sacred hoop. Called 'Dee' or 'Ndee,' the Apache hoop contains special powers that make it useful in a variety of ceremonies, although it is generally associated with healing and protection. The hoop is divided into four sections, traditionally by the tying of an eagle feather, symbolizing the four directions and the four seasons. Like most traditional Apache symbols, the hoop is usually one of the four sacred colors: black, green, yellow or white." About Apache Indian Symbols We have all seen Indian symbols used decoratively and symbolically. Just what do these Indian symbols depict? The symbols were used for many purposes. Often they were used to depict the language of life, nature and the Indian spirit. The American Indian viewed all things as having a spirit whether it was animate or inanimate, could be touched and seen or not. They thought of the universe as being all encompassing--holding the powers and secrets of deeper meaning. The symbols were used to evoke assistance from the spirits. The Native Americans had a great awareness of everything around them and they strived to live in harmony with their world and their universe. The Indians used symbols for many purposes and among them were on their war horses. They cherished their horses and used symbolism for protection, courage, strength and honor. The symbols were painted on the horse's body and head. Given the varied number of tribes, it is understandable that many symbols were used by the different tribes. However, they were used in keeping with the same belief in spirit and universe. The symbols often represented power, safety and success. They also represented the rider's affection for his horse. They symbols used conveyed profound beliefs and perceptions.

Image courtesy of the Oregon State Library.

The following originally appeared in The Collector's Guide to Albuquerque Metro Area - Volume 8

Collector's Guide - Follow this link to see the images and also some of the text quoted below:

Animals Used in Indian Symbolism

Alligator - Survival, strength and aggression.  Some Navajo Symbols What Does this Indian Symbol Mean?

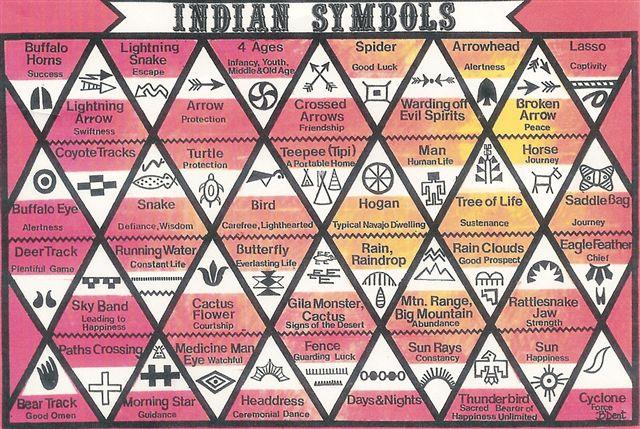

Decorative and symbolic, these designs are seen frequently

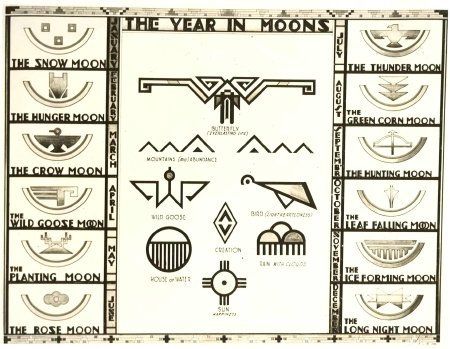

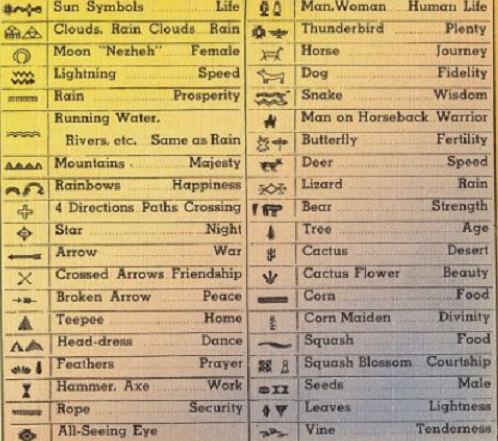

"Visitors to the Southwest are often intrigued by the variety and aesthetic appeal of the design elements used in Native American arts and crafts. The designs on Indian pottery, weavings, baskets and silver and stone jewelry are so intricate and carefully constructed, it is inconceivable they are not configurations holding some deeper meaning, shaped from a forgotten age, relics of an arcane language, or symbols of some old and secret religion. In all cultures, symbols borrow from experience, vision, and religion and become individualized through the creative process of the artist/symbol-maker. The designs used in the Southwest are from varied sources and they have been adapted and used by divergent tribes. Some have sifted in slowly as different groups arrived bringing their own inventory of designs; others have arrived with new technologies; still others have origins and, therefore, meanings, that will never be deciphered. The designs may be decorative, symbolic or combinations of both. Meanings may change from tribe to tribe. In one location a symbol may have meaning and in an adjacent tribe be used entirely as a decorative element. In short, every variation is possible.If a symbol is produced by one culture and interpreted by another, its meaning is far more often obscured than clarified. So it is with the symbols and designs of the Indian people of the Southwest. Over the years, both Native American designs (merely decorative forms) and symbols (a sign representing an idea, a quality or an association) have been subject to "interpretation" by non-Indian dealers and traders. Often, these interpretations are explained in terms of Anglo-European concepts that were nonexistent to the Native American. The result frequently bears little or no relationship to the true meaning of the symbols. Designs and symbols used in the Southwest actually have come from many places. Some design elements emerge out of the nature of the craft. The warp and weft of baskets or blankets produce a preponderance of geometrics, stars, swastikas and whirlwind designs. One of the most controversial of Native American designs is the swastika. While the swastika immediately brings to mind Nazi Germany, it is not only a native Southwestern design, it can be called a native design almost anywhere in the world. It is the result of basket weaving where the ends of a simple cross design are turned either to the right or left, depending on the direction of the weaving, to form a swastika. Its meanings are as diverse as its worldwide origins. Other designs also have been introduced with the technology of a craft. For example, a host of designs appear in metal dies which were derived from much older stamps used to decorate leather. These designs have been called by such fanciful names as rattlesnake jaws, Thunderbird tracks or a medicine man's eye. Others bear more prosaic names such as fence, tipi, mountain range, hogan, sun's rays, headdress or running water. However, in most instances they are purely decorative and their presence may be noted far back in history as elements of cultures other than that of the Native American. In the craft of silver smithing, the Thunderbird is used lavishly on stamped jewelry. The Thunderbird came to the Southwest via industrial dies furnished to Indian artists.  Northwest Coast styled Kwakwaka'wakw totem pole depicting a Thunderbird perched on the top. To Kwakwaka'wakw, different Thunderbirds are ancestors, whom they descend from. While it is a symbol of importance among the Plains Indians, this immense bird is neither characterized by the Southwestern Indians, nor do their myths offer explanations. Rather, the bird symbols of importance in the Southwest are the giant Knife-wing of the Zuni or the vulture, Kwatoko, of the Hopi. Nonetheless, the unknown individuals who supplied the dies for the silver felt that the Thunderbird was a "good Indian design" and so it appears on Southwestern jewelry and even on the beams of the Great Hall in the Albuquerque International Airport. The form of the silver naja, or pendant, at the end of the squash blossom necklace is traceable to Moorish Spain and even farther back in time to a device used to ward off the evil eye. Earlier still, it was found as boar's tusks hanging point-to-point decorating a Roman legionnaire's staff. In the same way, the squash blossom bead emerges from the pomegranate blossoms of Spain.Despite the multiple origins and mistaken interpretations of designs and symbols used in the Southwest, it is possible to recognize the meanings of many representations used in Native American works. The simplest of all representations is that which characterizes some element of the environment (bird, man, flower, horse, etc.) and is clearly distinguishable. Almost always it is used as a decorative device and nothing more, although its form may vary from tribe to tribe. These symbols are frequently seen on the pottery, weavings and jewelry made by Native Americans of the Southwest and generally can be interpreted as indicated. Several other symbols that arise from Native American cultures have become unrecognizable in their new "interpretations" including the butterfly. The snake and lightning or lightning arrow are considered by the native Southwesterner to be a single element as they are the same visual form. The snake does not symbolize "defiance" except possibly in New England, nor is its meaning "wisdom." Lightning is used by Anglo-Europeans indoctrinated in Greek mythology to denote swiftness, but among the Pueblo Indians snakes and lightning are equated with and symbolize rain, hence, fertility. These bird signs are often listed by traders as meaning "carefree or light-hearted," but the symbol is the macaw, a Zuni symbol for summer. This is but a glimpse of the rich inventory of Native American designs and symbols which are an integral part of antique and contemporary arts and crafts of this area and, in the form of petroglyphs throughout the Southwest, on the ancient rocks of this ancient land." Arrows - Arrows appear with many different symbolic representations. Meanings include direction, force, movement, and power. The import is much the same asthat of the bear and deer. they are a life force or pathway. In the animal spirit it is often referred to as the "heartline." Feathers - Feathers are symbols of prayers, marks of honor idea sources. Their use represents the creative force. For example, taken from birds and used on arrows, the line of the arrow should be straight and long as in the migration of birds. Goose feathers would be an excellent representation of this idea. One might look at the use of eagle feathers as honored or close to the gods. Pahos or Prayer Sticks - A prayer stick is a stick-shaped object used for prayer to the Creator or to the Kachinas. For example, the rituals of the Pueblo contain many prayers; thus the Zuñi have prayers for food, health, and rain. Prayer-sticks, that is sticks with feathers attached as supplicatory offerings to the "spirits", were largely used by the Pueblo. These sticks are usually made of cottonwood about seven inches long, and vary in shape, color, and the feather attached, according to the nature of the petitions, and the person praying. The stick is intended to represent the "god" to whom the feathers convey the prayers that are breathed into the "spirit" of the plumes. The Hopi Indians had a special prayer-stick to which a small bag of sacred meal was attached. Green and blue prayer-sticks are often found in the Pueblo graves and especially in the ceremonial graves of Arizona. These prayer-sticks are also found in Navajo designs. Circular Feather Arrangements - Circular feather arrangements are often found on pottery, in masks, prayer fans, dance costumes and on Plains "war bonnets." They are also used in decoration on buffalo hides, or to represent war honor stories, times of historic contact and other important periods of time. The sun or the creator are represented in the circular design. Plants, primary foodsources, tools, materials for basket making, healing provide many images. Flowers are usually connected with the sun. Common ones such as corn, symbol of life, squash, beans, beansprouts and seeds are very often found in pottery. The image here, is from a Navajo healing sandpainting, and each plant corresponds here to a compass direction as well. One unusual symbol, the open flower at the end of the "Squash blossoms" on Navajo necklaces, were not originally from squash at all. They were symbolic of the pomengranate, brought in by wealthy Spanish colonial settlers, and symbols of the new prosperity the Spanish introduced. As squash blossoms were already symbols of plenty, the new image took hold easily. Other plant images include trees, weeds (such as Devils Claw or Jimson Weed) and seed shapes. Whirling Logs, an ancient symbol from many cultures, the North American symbol depicted the cyclic motion of life, seasons and the four winds. Taken from the image of a tree in a whirlwind, this image is found in Navajop sand paintings frequently. It is considered a powerful medicine.Spirits and Myths

Yei or Yeii The Navajo yeii or yei means something along the lines of spirit, god, demon or monster. The most benevolent of such beings are the Diyin Diné'e or Holy People who are associated with the forces of nature. Yei bichei, or "maternal grandfather of the yei", is another name of Talking God who often speaks on behalf of the other Holy People. (He, along with Growling God, Black God, and Water Sprinkler, were the first four Holy People encountered by the Navajo.) He is invoked (along with eight other male yei) in the "Night Chant" or "Nightway" (Navajo: Tl'éé'jí), sometimes simply called "Yei bichei," a multiple-night ceremony in which masked dancers personify the gods. A rainbow yei, sometimes considered an aspect of the rain-god Water Sprinkler, is drawn around every sandpainting; his body curls around the south, west, and north sides to protect the painting from outside influences, and to protect the user from the power of the god depicted in the painting. He does not need to cover the east, because no evil can come from the east in Navajo thought. Kokopelli Kokopeltiyo, Kokopilau, Neopkwai'i (Pueblo), Ololowishkya (Zuni) and La Kokopel

Kokopelli is a fertility deity, usually depicted as a humpbacked flute player (often with a huge phallus and feathers or antenna-like protrusions on his head), who has been venerated by some Native American cultures in the Southwestern United States. Like most fertility deities, Kokopelli presides over both childbirth and agriculture. He is also a trickster god and represents the spirit of music.

Among the Hopi, Kokopelli carries unborn children on his back and distributes them to women; for this reason, young girls often fear him. He often takes part in rituals relating to marriage, and Kokopelli himself is sometimes depicted with a consort, a woman called Kokopelmana by the Hopi. It is said that Kokopelli can be seen on the full and waning moon, much like the "rabbit on the moon". Kokopelli also presides over the reproduction of game animals, and for this reason, he is often depicted with animal companions such as rams and deer. Other common creatures associated with him include sun-bathing animals such as snakes, or water-loving animals like lizards and insects. In his domain over agriculture, Kokopelli's flute-playing chases away the winter and brings about spring. Many tribes, such as the Zuni, also associate Kokopelli with the rains. He frequently appears with Paiyatamu, another flutist, in depictions of maize-grinding ceremonies. Some tribes say he carries seeds and babies on his back. In recent years, the emasculated version of Kokopelli has been adopted as a broader symbol of the Southwestern United States as a whole. His image adorns countless items such as T-shirts, ball caps, and key-chains. A bicycle trail between Grand Junction, Colorado, and Moab, Utah, is now known as the Kokopelli Trail. Origins and Development Kokopelli may have originally been a representation of ancient Aztec traders, known as pochtecas, who may have traveled to this region from northern Mesoamerica. These traders brought their goods in sacks slung across their backs and this sack may have evolved into Kokopelli's familiar hump; some tribes consider Kokopelli to have been a trader. These men may also have used flutes to announce themselves as friendly as they approached a settlement. This origin is still in doubt, however, since the first known images of Kokopelli predate the major era of Mesoamerican-Ancestral Pueblo peoples trade by several hundred years. Another theory is that Kokopelli is actually an anthropomorphic insect. Many of the earliest depictions of Kokopelli make him very insect-like in appearance. The name "Kokopelli" may be a combination of "Koko", another Hopi and Zuni deity, and "pelli", the Hopi and Zuni word for the desert robber fly, an insect with a prominent proboscis and a rounded back, which is also noted for its zealous sexual proclivities. A more recent etymology is that Kokopelli means literally "katsina hump". Because the Hopi were the tribe from whom the Spanish explorers first learned of the god, their name is the one most commonly used. Kokopelli is one of the most easily recognized figures found in the petroglyphs and pictographs of the Southwest. The earliest known petroglyph of the figure dates to about 1000 CE. The Spanish missionaries in the area convinced the Hopi craftsmen to usually omit the phallus from their representations of the figure. As with most katsinas, the Hopi Kokopelli was often represented by a human dancer. Kokopelli is a cottonwood sculpture often carved today. A similar humpbacked figure is found in artifacts of the Mississippian culture of the U.S. southeast. Between approximately 1200 to 1400 CE, water vessels were crafted in the shape of a humpbacked woman. These forms may represent a cultural heroine or founding ancestor, and may also reflect concepts related to the life-giving blessings of water and fertility.

The Twins  Complexity describes the role of twins in Indian Society. In the Myth's Encyclopedia Rather than enemies, twins in Native American mythology are often partners in a task or a quest. In myths from the Pacific Northwest, the twins Enumclaw and Kapoonis sought to obtain power over fire and rock from the spirits. Their activities became so threatening that the sky god made them into spirits themselves. Enumclaw ruled lightning, and Kapoonis controlled thunder." What's-Your-Sign.com Depicted in almost every emergence/creation story among the Southwestern Indian people. The twins are usually depicted as boys or small men who heroically overcam great odds to protect the people from monsters, drought, attack from other beings, animals, or many other problems. They illustrate the concept of duality: in life, in the natural world, everything exists in balance -- male/female, large/small, light/dark, good/evil. Here they are depicted as Father Sky/Mother Earth, from a Navajo sand painting. The Hand, represents the presence of man, his work, his acheivements, his legacy. It also represents the direction of the creative spirit through a man, as a vessel for the Creators power. Navajo Twins Usually described as Mother Earth and Sky Father twins, or Brother Sister twins, the Navajo Twins are powerful Native American symbols for creation and the evolution of creation itself. They also represent perfect balance.For More Information: Native American DesignsIndian Symbols |