Born August 11, 1835(1835-08-11)

Monterey, California

Died March 19, 1875 (aged 39)

San Jose, California

Conviction(s) Murder

Penalty Death by hanging

Status Deceased

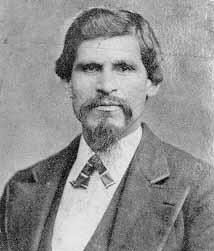

Tiburcio Vásquez (August 11, 1835-March 19, 1875) was a California bandit who was active in California from 1857 to 1874. The Vasquez Rocks, 40 miles north of Los Angeles, were one of his many hideouts and are named for him.

Early Life

Tiburcio Vásquez was born in Monterey, California, a descendant of some of the earliest settlers of California. His great-grandfather had arrived in California with the DeAnza expedition of 1776. Vásquez was slightly built, about 5 feet 7 inches in height. His family sent him to school, and he was fluent in both English and Spanish.

At the age of 17, Vásquez was present at the slaying of Constable William Hardmount in a fight with Vásquez's cousin at a fandango. Vásquez denied any involvement, but fearing arrest, he became an outlaw. Vásquez would later claim his crimes were the result of discrimination by the norteamericanos and insist that he was a defender of Mexican-American rights.

By 1856, he was actively rustling horses. A sheriff's posse caught up with him near Newhall, and he spent the next five years behind bars in San Quentin prison. After his release, Vásquez made attempts to be law abiding, but eventually returned to crime. He was captured after a robbery in 1867 and sent to prison again for a short time.

Final Years

In 1871, Vásquez was wounded after a stage coach robbery, but avoided capture. In 1873 he gained statewide notoriety. Vásquez and his gang stole $200 from Snyder's Store in Tres Pinos, in San Benito County, killing three innocent bystanders in the process. Posses began searching for him, and Governor Newton Booth placed a $1,000 reward on his head.

Vásquez moved to Southern California, where he was less well known. With his two most trusted men, he rode over Tejon Pass, through the Antelope Valley, and rested at Jim Heffner's ranch at Elizabeth Lake. Vásquez' brother, Francisco, lived nearby. After resting, Vásquez rode on to Littlerock Creek, which would become his first Southern California hideout.

Vásquez returned to the San Joaquin Valley, and committed another robbery at Kingston in Fresno County on December 26, 1873, making off with $2,500 in cash and jewelry.

Governor Booth was now authorized by the California state legislature to spend up to $15,000 to bring Vásquez to justice. Posses were formed in Santa Clara, Monterey, San Joaquin, Fresno, and Tulare Counties. In January 1874, Booth offered $3,000 for Vásquez's capture alive, and $2,000 if he was brought back dead. These rewards were increased in February to $8,000 and $6,000, respectively. Alameda County Sheriff Harry Morse was assigned specifically to track down Vásquez.

Heading towards Bakersfield, Vásquez and his gang rode south to the rock promontory now known as "Robbers Roost" after him. From there, the gang could rob coaches from the silver mines near Owens Lake. However, pickings were poor. Vásquez also shot and wounded a man who didn't obey his orders. Because of this, the stages would add a shotgun rider beside the driver.

The gang moved to Elizabeth Lake and Soledad Canyon, robbing a stage of $300, stealing six horses and a wagon near present day Acton, and robbing lone travelers. Vásquez was believed to be hiding out at Vasquez Rocks. For the next two months, he escaped attention. However, he then made an error that led to his capture.

Capture

Vásquez took up residence in the Hollywood Hills at "Greek George's" ranch, located on the San Fernando Valley side of the Cahuengas Mountains. Greek George was a former camel driver for General Beale in the Army Camel Corps. Allegedly, Vásquez seduced and impregnated his own niece. Either the girl's family or Greek George's wife's family betrayed Vásquez to Los Angeles Sheriff William Roland. Roland led a posse to the ranch and captured Vásquez on May 13, 1874. He was caught at a location which is now in, or close to, West Hollywood, CA. The ranch of "Greek George" by one account was at or near the present intersection of Fountain Ave. and King's Road in West Hollywood. This was, ironically, very close to where the movie industry would, in a few decades, set up shop.

Vásquez remained in the Los Angeles County jail for nine days. He had numerous requests for interviews by many newspaper reporters, but agreed to see only three: two from the San Francisco Chronicle and one from the Los Angeles Star. He told them his aim was to return California to Mexican rule. He insisted he was an honorable man and said he had never killed anyone.

In late May, Vásquez was moved by steamship to San Francisco, California. He would eventually stand trial in San Jose. Vásquez quickly became a celebrity among many of his fellow Hispanic Californians. He admitted he was an outlaw, but again denied he had ever killed anyone. A note written by Clovidio Chavez, one of his gang members, was dropped into a Wells Fargo box. Chavez wrote that he, not Vásquez, had shot the men at Tres Pinos. Nevertheless, in January 1875 Vásquez was sentenced to hang for murder. His trial had taken four days and the jury deliberated for two hours before finally finding him guilty of two counts of murder in the Tres Pinos robbery.

Visitors still flocked to Vásquez's jail cell, many of them women. He signed autographs and posed for photographs. Vásquez sold the photos from the window of his cell and used the money to pay for his legal defense. After his conviction, he appealed for clemency. It was denied by Governor Romualdo Pacheco. Vásquez calmlymet his fate in San Jose on March 17, 1875. He was 39 years old.

Quotes

"A spirit of hatred and revenge took possession of me. I had numerous fights in defense of what I believed to be my rights and those of my countrymen. I believed we were unjustly deprived of the social rights that belonged to us." (Dictated by Vásquez to explain his actions)

Vásquez was asked just before his execution, "Do you believe in an afterlife?" He replied, "I hope so... for then soon I shall see all my old sweethearts again." The only word he spoke on the gallows was pronto - soon.

Legacy

Even today, Tiburcio Vásquez remains controversial. He is seen as a hero by some Mexican-Americans for his defiance of what he viewed as unjust laws and discrimination. Others regard him simply as a colorful outlaw.

|