Medical Index Home | First Posted: Aug 7, 2010 Last Update:Jan 21, 2020 | |

All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 3Continued: Conformation of the Front and Hind Legs

The Front Legs The Cannon and Tendons

The cannon bone is referred to as the weight bearing bone. The circumfrence of the cannon, just under the knee, is a guide to the horse's abillity to bear weight and do hard work. It is often referred to as the 9" bone. Long Cannon BoneThe cannon is long between the knee and fetlock, making the knees appear high relative to the overall balance of the horse and reduces the muscular pull of the tendons on the lower leg. Uneven terrain or unlevel foot balance will magnify the stress on the carpus since lengthy tendons are not as stabilizing to the lower limb as shorter ones. It also increases the weight on the end of the limb, contributing to less efficient and less stable movement. Added weight to front legs increases the muscular effort needed in picking up a limb, leading to hastened fatigue. There is an increase in tendon/ligament injury with long cannon bones, especially when the horse is also tied-in above the knee. Horses with long cannons are best for flat racing short distances. Short Cannon BoneCannon is relatively short from fetlock to knee as compared to knee to elbow. This conformation is desirable in any performance horse. A short cannon bone improves the ease and power of the force generated by the muscles of a long forearm or gaskin. Enables an efficient pull of the tendons across the back of the knee or point of hock to move the limb forward and back. Also reduces the weight of the lower leg so less muscular effort is needed to move the limb, which contributes to speed, stamina, soundness, and jumping ability. Rotated Cannon BoneThe cannon rotates to the outside of the knee so it appears twisted in its axis relative to knee. It may still be correct and straight in alignment of joint, but is more often associated with appearance of carpus valgus. This rotation places excess strain on the inside of the knee and lower joints of the leg, potentially leading to soundness issues, although this is not common.

The cannons are set to the outside of the knee so an imaginary plumb line does not fall through middle. Offset knees often cause excessive strain on the lateral surfaces of the joints from the knee down and on the outside portions of the hoof. There is an exaggerated amount of weight supported by the medial splint bone, leading to splints. The horse is most suited for non-speed activities like pleasure riding, driving, and equitation. Tied-in Below the KneeThe cannon, just below the knee, appears "cut out" with a decreased tendon diameter. Rather than parallel with cannon, tendons are narrower than the circumference measured just above the fetlock. This affects speed event (racing, polo) and concussion events (steeplechase, jumping, eventing, endurance). It limits the strength of the flexor tendons that are needed to absorb the concussion and diffusion of impact through the legs, making the horse more prone to tendon injuries, especially at the midpoint of the cannon or just above. The leverage of muscle pull is decreased as the tendons pull against the back of knee rather than a straight line down back of leg. This reduces power and speed. This knee conformation is associated with a reduced size in the accessory carpal bone the back of knee over which the tendons pass. The small joints are prone to injury and does not provide adequate support for the column of leg while under weight-bearing stress.The horse is most suited for sports that shift the animal's weight to the rear or that do not depend on perfect forelimb conformation (dressage, driving, cutting). The Front Legs-The Knee

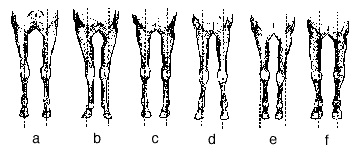

One or both knees deviate inward toward each other, with the lower leg angles out, resulting in a toed-out stance. Occurs because of an unequal development of the growth plate of distal radius, with the outside growth plate growing faster than inside. The bottom of the forearm seems to incline inward. Any horse can inherit this, but it may also be acquired from imbalanced nutrition leading to developmental orthopedic disease (DOD) or a traumatic injury to growth plate. The horse is most suited for pleasure riding, low-impact, and low speed events. The medial supporting ligaments of the carpus will be under excess tension. May cause soundness problems in the carpals or supporting ligaments. Horse also tends to toe-out, causing those related problems. Some research is beginning to indicate that deviation of the front leg in this way will reduce the injuries to horses with sport use, especially racing, the research done in Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses. Even in his statue, Seabiscuit was visibly over at the knees/Bucked, Sprung, or Goat Knees/Over at the Knee

Knee inclines forward, in front of a plumb line, when viewed from the side. Often a result of an injury to the check ligament or to the structures at the back of the knee. The column of the leg is weakened. Thus, the horse is apt to stumble and lose balance due to the reduced flexibility and from the knee joints that always are "sprung." If congenital, often associated with poor muscle development on the front of the forearms, which limits speed and power. More stress is applied to the tendons, increasing the risk of bowed tendons. The angle of attachment of the DDF and check ligament is increased, predisposing the check ligament to strain. Tendons and fetlock are in an increased tension at all times, so the horse is predisposed to injury to the suspensory (desmitis) and sesamoid bones. If the pasterns are more upright there is further stress.

The knee inclines backward, behind a straight plumb line dropped from the middle of the forearm to the fetlock. Usually leads to unsoundness in horses in speed sports. Places excess stress on the knee joint as it overextends at high speeds when loaded with weight. Backward angle causes compression fractures to the front surfaces of the carpals, and may cause ligament injury within knee. Worsens with muscle fatigue as the supporting muscles and ligaments lose their stabilizing function. Calf-knees weaken the mechanical efficiency of the forearm muscles as they pull across the back of the carpus, so a horse has less power and speed. The tendons and check ligament assume an excess load so the horse is at risk for strain. Often the carpals are small and cannot diffuse the concussion of impact. The horse should have good shoeing, eliminating LTLH (long-toe, low-heel) syndrome. Sports that have more hindquarter function, like dressage, or slow moving activities like pleasure riding, are best for this horse. The Front Legs-The Fetlock

An angular limb deformity that creates a toed-out appearance from the fetlock down. A fairly common fault Creates excess strain on one side of the hoof, pastern and fetlock, predisposing the horse to DJD, ringbone, foot soreness or bruising. The horse will tend to wing, possibly causing an interference injury. May damage splint or cannon bone. This conformation diminishes the push from rear legs, as symmetry and timing of the striding is altered with the rotated foot placement, particularity at the trot. Thus, stride efficiency is affected to slow the horse's gait. The horse is unable to sustain years of hard work.

An angular limb deformity causing a pigeon toed appearance from the fetlock down, with the toe pointing in toward the opposite limb. Horse is most suited for pleasure riding, non-impact, low-speed, and non-pivoting work. These horses tend to paddle, creating excess motion and twisting of the joints with the hoof in the air. This is unappealing in show horse, wasteful energy, which reduces the efficiency of the stride, so the horse fatigues more quickly. The hoof initially impacts ground on inside wall, causing excess stress on the inside structures of the limb, leading to ringbone (DJD) and sole or heel bruising in inside of hoof. The Hindlegs

Hocks

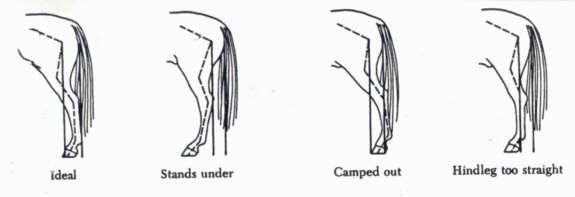

Results from a relatively short tibia with a long cannon. Ideally, hocks are slightly higher than the knees, with the point of hock level with the chestnut of the front leg. Hocks will be noticeable higher in horse with this conformation. The horse may have a downhill balance with the croup higher than the withers. See especially in Thoroughbreds, racing Quarter Horses, and Gaited horses. With this conformation, the horse can pull the hind legs further under the body, so there is a longer hind end stride, but the animal may not move in synchrony with the front. This will create an inefficient gait, as the hind end is forced to slow down to let the front end catch up, or the horse may take high steps behind, giving a flashy, stiff hock and stifle look. May cause forging or overreaching. Often results in sickle hock conformation. Long Gaskin/Low HocksLong tibia with short cannons. Creates an appearance of squatting. Usually seen in Thoroughbreds and stock horses. A long gaskin causes the hocks and lower legs to go behind the body in a camped-out position. The leg must sickle to get it under the body to develop thrust, causing those related problems. The long lever arm reduces muscle efficiency to drive the limb forward. This makes it hard to engage the hindquarters. The rear limbs may not track up and the horse may have a reduced rear stride length, forcing the horse to take short steps. The horse is best used for galloping events, sprinting sports with rapid takeoff for short distance, or draft events. Hocks Too SmallHock appears small relative to the breadth and size of adjacent bones. Same principals with knees too small. The joints are a fulcrum which tendons and muscles pass over for power and speed, and large joints absorb concussion and diffuse the load of the horse. Small joints are prone to DJD from concussion and instability, especially in events where the horse works off its hocks a lot. A small hock does not have a long tuber calcis (point of hock) over which the tendons pass to make a fulcrum. This limits the mechanical advantage to propel the horse at speed. The breadth of the gaskin also depends on hock size, and will be smaller. Cut Out Under the HockFront of the cannon, where it joins the hock, seems small and weak compared to the hock joint. In the front end, its called "tied in at knee." Mainly affects sports that depend on strong hocks (dressage, stock horse, jumping). Reduces the diameter of the hock and cannon, which weakens the strength and stability of the hocks. Means a hock is less able to support a twisting motion (pirouettes, roll backs, sudden stops, sudden turns). The horse is at greater risk for arthritis or injury in hock. Slightly Camped Out BehindCannon and fetlock are "behind" the plumb line dropped from point of buttock. Associated with upright rear pasterns. Seen especially in Gaited horses, Morgans, and Thoroughbreds. Rear leg moves with greater swing before the hoof contacts the ground, which wastes energy, reduces stride efficiency, and increases osculation and vibrations felt in joints, tendons, ligaments, and hoof. May cause quarter cracks and arthritis. Difficult to bring the hocks and cannons under unless the horse makes a sickle hocked configuration. Thus, the trot is inhibited by long, overangulation of the legs and the horse trots with a flat stride with the legs strung out behind. It is difficult to engage the back or haunches, so it is hard to do upper level dressage movements, bascule over jumps, or gallop efficiently.

The hind leg slants forward, in front of the plumb line, when viewed from the side. The cannon is unable to be put in vertical position. Also called "curby" hock, as it is associated with soft tissue injury in the rear, lower part of the hock. Limits the straightening and backward extension of hocks, which this limits push-off, propulsion, and speed. There is overall more hock and stifle stress. Closed angulation and loading on the back of the hock predisposes the horse to bone and bog spavin, thoroughpin, and curb.

Angles of the hock and stifle are open. The tibia is fairly vertical, rather than having a more normal 60 degree slope Common, usually seen in Thoroughbreds, steeplechasers, timber horses, eventers, and hunter/jumpers. In theory, sickle hocks facilitate forward and rearward reach as the hock opens and closes with a full range of motion without the hock bones impinging on one another. This led to selective breeding of speed horses with straight rear legs, especially long gaskins. The problem is that this breeding has been taken to the extreme. Tension on the hock irritates the joint capsule and cartilage, leading to bog and bone spavin. Restriction of the tarsal sheath while in motion leads to thoroughpin. A straight stifle limits the ligaments across the patella, predisposing the horse to upward fixation of the patella, with the stifle in a locked position, which interferes with performance and can lead to arthritis of the stifle. It is difficult for the horse to use its lower back, reducing the power and swing of the leg. Rapid thrust of the rear limbs causes the feet to stab into the ground, leading to bruises and quarter cracks.

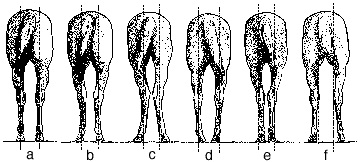

Hocks deviate from each other to fall outside of plumb line, dropped from point of buttocks, when the horse is viewed from behind. Most commonly seen in Quarter Horses with a bulldog stance. Hoof swings in as the horse picks up its hocks and then rotates out, predisposing the animal to interference and causing excess stress on lateral hock structures, predisposing the horse to bog and bone spavin, and thoroughpin. The twisting motion of the hocks causes a screwing motion on the hoof as it hits the ground, leading to bruises, corns, quarter cracks, and ringbone. The horse does not reach forward as well with the hind legs because of the twisting motion of the hocks once lifted, and the legs may not clear the abdomen if the stifles are directed more forward than normal. This reduces efficiency for speed and power. Cow Hocks/Medial Deviation of the Hocks/Tarsus ValgusHocks deviate toward each other, with the cannon and fetlock to the outside of the hocks when the horse is viewed from the side. Gives the appearance of a half-moon contour from the stifle to hoof. Often accompanied by sickle hocks. Fairly common, usually seen in draft breeds. Disadvantages to trotting horses, harness racers, jumpers, speed events, and stock horses. Many times Arabians, Trakehners, and horses of Arabian descent are thought to have cow hocks. But really the fetlocks are in alignment beneath the hocks, so they are not true cow hocks. A slight inward turning of hocks is not considered a defect and should have no effect. A horse with a very round barrel will be forced to turn the stifles more out, giving a cow-hocked appearance. Medial deviation in true cow hocks causes strain on the inside of the hock joint, predisposing the horse to bone spavin. Abnormal twisting of pastern and cannon predisposes fetlocks to injury. More weight is carried on medial part of hoof, so it is more likely to cause bruising, quarter cracks, and corns. The lower legs twist beneath the hocks, causing interfering. The horse develops relatively weak thrust, so speed usually suffers. Conformation of the PasternsThe angle of the pasterns is best at a moderate slope (about 50 degrees) and moderate length.

The pasterns are long (more than 3/4 length of cannon) relative to rest of leg. This defect affects long-distance and speed sports. Long pasterns have been favored because they can diffuse impact, giving a more comfortable ride. However, excess length puts extreme tension on the tendons and ligaments of the back of the leg, predisposing the horse to a bowed tendon or suspensory ligament injury. The suspensory is strained because fetlock is unable to straighten as horse loads the limb with weight. The pasterns are weak and unable to stabilize fetlock drop, so the horse is predisposed to ankle injuries, espescially in speed events where the sesamoids are under extreme pressure from the pull of the suspensory. This can cause sesamoid fractures and breakdown injuries. May be associated with high or low ringbone. Increased drop of fetlock causes more stress on pastern and coffin joints, setting up conditions for arthritis. There is a delay time to get the feet off the ground to accelerate, and thus long pasterns make the horse poor for speed events. The horse is best for pleasuring riding, equitation, and dressage. A horse's pasterns are short if they are less than 1/2 length of cannon. The pasterns are upright if they are angled more toward the vertical. A long, upright pastern has the same performance consequences as short and upright. Most commonly seen in Quarter Horses, Paints, and Warmbloods The horse is capable of rapid acceleration, but is restricted to a short stride. They excel in sprint sports. The short stride is a result of both a short pastern and upright shoulder, creating a short, choppy stride with minimal elasticity and limited speed. Short pasterns have less shock-absorption, leading to more a jarring ride and amplified stress on the lower leg. The concussion is felt over the navicular apparatus, so the horse is more at risk for navicular disease, high or low ringbone, and sidebone. Also windpuffs and windgalls occur from chronic irritation within fetlock or flexor tendon sheath. The horse has reduced mechanical efficiency for lifting and breaking over the toe, so it may trip or stumble. The horse is best for sprint sports like Quarter Horse racing, barrel racing, roping, reining, and cutting. Conformation of the Feet and Base

Horse Hoof Conformation A excellent article on the base of the horse and the feet of the horse

The horse's feet are turned away from each other. Common fault Causes winging motion that may lead to interfering injury around fetlock or splint. As horse wings inward, there is a chance that he may step on himself, stumble, and fall. A horse that is "tied in behind the elbow" has restricted movement of the upper arm because there is less clearance for the humerus (it angles into the body too much). Reduced clearance of legs causes horse to toe-out to compensate. Toe-In/Pigeon-Toed (See "c" in above chart)Toes of hooves face in toward each other. Common fault. Pigeon-toes cause excess strain on the outside of the lower structures of the limb as the horse hits hard on the outside hoof wall. This often leads to high or low ringbone. The horse is also predisposed to sidebone and sole bruising. The horse moves with a paddling motion or winging motion, wasting energy and hastening fatigue so that he has less stamina.

Horse Hoof Conformation

A excellent article on the base of the horse and the feet of the horse

Stresses the outside structures of the limb, especially the outside of the foot. Causes a winging motion, leading to interfering. Predisposes the horse to plaiting. The horse tends to hit himself more when fatigued. Base narrow, toed-in: Excessive strain on the lateral structures of fetlock, pastern, and outside of hoof wall. Causes the horse to paddle. The horse is least suited for speed or agility sports.

Base Wide, Toed-Out - The horse lands hard on the outside of the hoof wall and places excessive strain on the medial structures of the fetlock and pastern, leading to ringbone or sidebone, and potentially spraining structures of the carpus. The horse will wing in, possibly leading to an interference injury or overload injury of the splint bone. Base Wide, Toed-In - The horse lands hard on the inside hoof wall, placing stress on the medial structures of limb. The horse will also paddle. Stands Close Behind/Base Narrow BehindWith a plumb line from the point of buttock, the lower legs and feet are placed more toward the midline than the regions of hips and thigh, with a plumb line falling to the outside of the lower leg from the hock downward. Usually accompanied by bow-legged conformation. A fairly common fault, especially in heavily muscled horses like Quarter Horses. The hooves tend to wing in, so the horse is more likely to interfere. If the hocks touch, they may also interfere. The horse cannot develop speed for rapid acceleration. The outside of the hocks, fetlocks, and hooves receive excessive stress and pressure. This leads to DJD, ligament strain, hoof bruising, and quarter cracks. The horse is best for non-speed sports and those that do not require spins, dodges, or tight turns. The Hoof

Feet Too SmallRelative to size and body mass, the feet are proportionately small There is a propensity to breed for small feet in Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, and American Quarter Horses. A small foot is less capable of diffusing impact stress with each footfall than a larger one. On hard footing, the foot itself receives extra concussion. Over time, this can lead to sole bruising, laminitis, heel soreness, navicular disease, and ringbone. Sore-footed horses take short, choppy strides, so they have a rough ride and no gait efficiency. If the horse has good shoeing support, it can comfortably participate in any sport, although it is more likely to stay sound in sports that involve soft footing.

Large in width and breadth relative to body size and mass. May have slight pastern bones relative to large coffin bone. Flat feet limit the soundness of the horse in concussion sports (jumping, eventing, steeplechase, distance riding). Without proper shoeing or support, the sole may flatten. Low, flat soles are predisposed to laminitis or bruising. The horse takes on a choppy, short stride. It is hard for the horse to walk on rocky or rugged footing without extra protection on the hoof. A large foot with good cup to sole is ideal foot for any horse. There is less incidence of lameness, and it is associated with good bone. For flat footed horses, sports with soft footing and short distances like dressage, equitation, flat racing, barrel racing are best. Mule Feet - Horse has a narrow, oval foot with steep walls Mule feet are fairly common, usually seen in American Quarter Horses, Arabians, Saddlebreds, Tennessee Walkers, Foxtrotters, and Mules. A mule foot provides little shock absorption to foot and limb, creating issues like sole bruising, corns, laminitis, navicular, sidebone, and ringbone. Not all horses have soundness issues, especially if they are light on the front end and have very tough horn. Because the hind end provides propulsion, it is normal to see more narrower hooves on back compared to front Soft-terrain sports like polo, dressage, arena work (equitation, reining, cutting), and pleasure riding are most suitable.

The slope of hoof wall is steeper than the pastern, often associated with long, sloping pasterns tending to the horizontal, which breaks the angulation between pastern and hoof. Usually seen in rear feet, esp in post-legged horses. Coon feet are sometimes due to a weak suspensory that allows the fetlock to drop. Quite uncommon, it particularly affects speed sports and agility sports Coon feet create similar problems as too long and sloping pasterns (the horse prone to run-down injuries on back of fetlock). If foot lift off is delayed in bad footing, ligament and tendon strain and injury to the sesamoid bones is likely. Weakness to supporting ligaments due to post leg or injury to suspensory will result in a coon-foot as the fetlock drops. The horse is most suited for low-speed exercise like pleasure riding or equitation.

The slope of the front face of hoof exceeds 60 degrees. Horse often has long, upright heels. May be from contracture of DDF (deep digital flexor tendon) that was not addressed at birth or developed from nutritional imbalances or trauma. Fairly common, best to use horse in activities done in soft-footing and those that depend on strong hindquarter usage Various degrees of angulation, from slight to very pronounced. Horses with obvious club feet land more on the toes, causing toe bruising or laminitis. The horse generally does poorly at prolonged exercise, especially if on hard or uneven terrain (eventing, trail riding). Because the toe is easily bruised, the horse moves with a short, choppy stride, and may stumble. The horse is a poor jumping prospect due to trauma incurred on impact of landing.

The heels appear narrow and the sulci of frogs are deep while the frog may be atrophied. May be seen in any breed, but most common in American Quarter Horses, Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, Tennessee Walkers, or Gaited horses. Contracted heels are not normally inherited, but a symptom of limb unsoundness. A horse in pain will protect the limb by landing more softly on it. Over time, the structures contract. The source of pain should be explored by a vet. Contracted heels create problems like thrush. The horse loses shock absorption ability, potentially contributing to the development of navicular syndrome, sole bruising, laminitis, and corns. Heel expansibility may also be restricted, causing lameness from pressure around the coffin bone and reduced elasticity of the digital cushion. Horse is best used for non-concussion sports.

Wall is narrow and thin when viewed from bottom. Often associated with flat feet or too small feet. Common, especially in American Quarter Horses, Thoroughbreds, and Saddlebreds. Thin walls reduce the weight-bearing base of support, and are often accompanied by flat or tender soles that easily bruise. The horse is subject to developing corns at the angles of the bar. The horse tends to grow long-toes with low heels, moving the hoof tubules in horizontal direction, and so it reduces shock absorption ability and increases the risk of lameness. Less integrity for expansion and flexion of hoof, making it more brittle and prone to sand and quarter cracks. Narrow white line makes it hard to hold shoes on. Horse does best when worked only on soft footing.

One side of the hoof flares towards its bottom, relative to the steep appearance of the other side. Flared surface is concave. Horse is best to use in low-impact or low-speed sports May be conformationally induced from angular limb deformity or malalignments of the bones within the hoof. These conformational problems cause excess strain on one side of hoof making it steepen, while the side with less impact grows to a flare. The coronary band often slopes asymmetrically due to pushing of hoof wall and coronet on steep side, which gets more impact than flared. May develop sheared heels, causing lameness issues, contracted heels and thrush. May be acquired from imbalanced trimming methods over time that stimulate more stress on one side of foot. Chronic lameness may make the horse load the limb unevenly, even if the lameness may be in hock or stifle. The Horse's Overall Balance and Bone

Insufficient BoneMeasuring the circumference of the top of the cannon bone, just below the knee, gives an estimation of the substance. Ideally a 1,000 lb horse should have 7-8 inches. Insufficient is less than 7 inches for every 1,000 lb of weight. A horse with insufficient bone is more at risk for injury (within the bones, joints, muscle, tendons, ligaments, and feet). Repeated impact creates soundness issues, especially in those sports with a lot of concussion (jumping, galloping, racing, long distance trail). Track horses get bucked shins, event and trail horses get strained tendons and ligaments. Light-Framed/Fine BonedSubstance of long bones is slight and thin relative to the size and mass of the horse. Especially noticed in the area of the cannon and pastern. Seen especially in show horses, halter horses in non-performance work, Paso Finos, Gaited horses, and Thoroughbreds. Affects the longevity of performance horses. Does not provide ample support for bulky musculature and there is a lack of harmony visually. Theoretically, a lighter frame reduces the weight on the end of the limbs, making it easier to pick up the legs and move freely across the ground. However, with a lot of speed and impact work, light bone suffers concussion injury, leading to bucked shins, splints, " stress fractures. Tendons, ligaments, and muscles have less lever system to pull across to effectively use or develop muscle strength for power and stamina. It is best to match the horse with a petite & lean rider. It is best to use the horse for pleasure, trail, driving, non-impact sports, and non-speed work. Long bones are big, wide, and strong in a horse with either light or bulky muscled appearance. Advantageous for any sport, the horse tends to hold up well. The horses tend to be rugged and durable, capable of carrying large weights relative to size. Big, solid bones provide strong levers for the muscles to pull against to improve efficiency of motion, thus minimizing the effort of exercise and reduces the likelihood of fatigue, contributing to endurance. May add mass to each leg, and consequently slightly hinder speed at the gallop when flat racing.

The peak of the withers is higher than the peak of the croup when the horse is square. This is commonly referred to as built uphill. Uphill build is very advantageous in dressage, eventing, etc as the horse has an easier time engaging the hind end. However true uphill or downhill build depends on the levelness of the spine. Many breeds characteristically have high and prominent withers, such as the TB. In these horses the withers may be higher than the croup giving the impression of an uphill build while the horse's actual spine levelness is downhill. Common in well-built warmbloods.

The peak of the croup is higher than the peak of the withers. This is less desirable than a horse with higher withers. Seen in any breed but especially in Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds, and Quarter Horses. Young horses are usually built this way. More weight is placed on the forehand, reducing the front-end agility. Muscles must work harder to lift the forehand, leading to muscular fatigue. It is difficult to raise the forehand at the base of a jump for liftoff. At speed, more work of loins, back and front end is needed to lift the forelimbs. Increases concussion on the front legs, so the horse is at greater risk of front-end lameness. Greater jar on the rider. Tends to throw the saddle " rider toward the shoulders, leading to chaffing, pressure around withers, and restricted shoulder movement.

This horse is too tall in context to the rider. The ability to communicate with the seat and leg is affected. The rider looks awkward. A tall horse may not be as handy or agile.

The horse may not be able to maintain balance (top heavy), so it may be more prone to tripping or falling if the rider loses a balanced seat position. Heaviness of the rider in proportion to horse's mass can cause a sore back and loins " rapid muscle fatigue in general, reducing stamina. The horse may be unwilling to jump or run fast because of extreme work to carry large rider on back, which forces a horse to overuse the muscles while the front limbs receive excess strain and impact with a risk of developing lameness problems. It is difficult for a rider to find point of balance, as the rider's legs barely touch a horse's narrow sides. Thus it is hard for rider to use leg aids. Horse is best used for pleasure, non-speed work, non-jumping sports, and sports that do not require quick changes of direction/speed. Horse should carry less than 20% of body weight (rider/tack) as a general rule of thumb. Horses with short backs and more dense, compact bone structure may be able to carry more weight. For More Information: StifleEquine Lameness Lameness Gaited Horse Leg Problems Most Prevalent in Horses All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 1 All About the Horse's Conformation/Part 2 The Conservative Approach for Healing Horses |