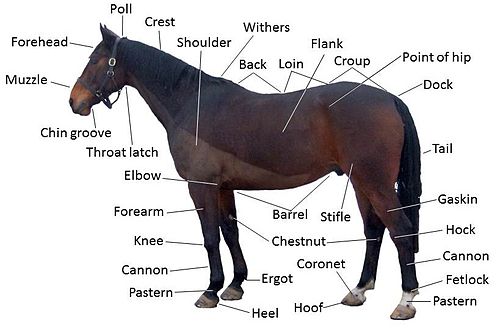

Conformationally the horse's neck is really important. I was once told that a horse's neck could never be too long. Horse people always have at least one opinion on every horse related subject--usually more--none necessarily correct! The neck is absolutely fundamental to the way a horse moves. There are seven cervical vertebrae connected to form an S-shape from poll to withers. The top two vertebrae are designed to support and move the head. The other five curve downward to the base of the underside of the neck, at the chest. They are situated to allow adjacent thoracic vertebral processes to jut upward. This forms the withers. The equine neck is a complex structure in which more than a hundred muscles support and move seven very large bones called vertebrae. The sensitive spinal cord and peripheral nerves intersect each vertebrae before continuing down the forelimbs. How a horse's neck comes out at the shoulder is important. Also, a clean throat latch is important. Taking into consideration the foregoing, think about the many nerves that are involved. The neck comprises 6% of the horse's body mass. It all affects a horse's "way of going" or how a horse moves. Not yet mentioned is that the equine neck also houses the trachea (windpipe), esophagus, jugular vein, many tendons and ligaments, and cartilage. Deep within the vertebral column is the spinal cord. All of this affects a horse's soundness.

"Neck Length and Position

A neck of ideal length is about one third of the horse's length, measured from poll to withers, with a length comparable to the length of the legs. An ideally placed neck is called a horizontal neck. It is set on the chest neither too high nor too low, with its weight and balance aligned with the forward movement of the body. The horse is easy to supple, develop strength, and to control with hand and legs aids. Although relatively uncommon, it is usually seen in Thoroughbreds, American Quarter Horses, and some Warmbloods. Horizontal neck is advantageous to every sport, as the neck is flexible and works well for balancing. A short neck is one that is less than one third the length of the horse. Short necks are common, and found in any breed. A short neck hinders the balancing ability of the horse, making it more prone to stumbling and clumsiness. A short neck also adds more weight on the forehand, reducing agility.

Bull neck: short and thick. A short, thick, and beefy neck with short upper curve is called a bull neck. The attachment to its body is beneath the half-way point down the length of shoulder. Bull neck is fairly common, especially in draft breeds, Quarter Horses, and Morgans. Bull neck makes it more difficult to maintain balance if the rider is large and heavy or out of balance, which causes the horse to fall onto its forehand. Without a rider, the horse usually balances well. A bull neck is desirable for draft or carriage horses, so as to provide comfort for the neck collar. The muscles of the neck also generate pulling power. A horse with bull neck is best for non-speed sports. Bull neck is not considered a deformity.

A long neck is one that is more than one third the length of the horse. Long necks are common, especially in Thoroughbreds, Saddlebreds, and Gaited Horses. A long neck may hinder the balancing ability of the horse, and the horse may fatigue more quickly as a result of the greater weight on its front end. The muscles of a long neck are more difficult to develop in size and strength. A long neck needs broad withers to support its weight. It is easier for a long necked horse to fall into the bend of an S-curve than to come through the bridle, which causes the horse to fall onto its inside shoulder. This makes it difficult for the rider to straighten. A horse with this trait is best used for jumping, speed sports without quick changes of direction, or for straight line riding such as trail riding.

Note: You may hear the term "artificial gait" used to define the running walk, slow gait, pace and rack. They are very natural to specific breeds of horses (gaited horses), and are genetically passed on and can often be seen from birth. In that sense they are not really artificial gaits. A horse with natural artificial gaits does not need mechanical influence, not even special shoeing. Our two horses, A Patchy, a Spotted Mountain Saddle Horse, and Rusty, a Kentucky Mountain Saddle Horse, have natural gaits and are barefoot. (all 4-around!) Some breeds that are identified as "gaited" are: Tennessee Walkers, Rackers, Icelandic Horses, Fast tolt/Icelandic Horse Paso Finos, Rocky Mountain Horses, Kentucky Mountain Horses, Spotted Mountain Horses, the Mountain Pleasure Horse; some Morgans, Saddlebreds and Standardbreds can be naturally gaited, some not. Also, many ponies and some mules are also gaited. For quite a complete list follow this link: Horse Hints Horse Breeds Index (450+ Breeds). Look for the breeds that have the "green ball." Alos, this HorseHints.org link will explain all about Horse Gaits Regular and Artificial (Footfalls). It is an excellent resource on how a horse moves.

To view Extension's video on the artificial gaits follow this link: Artificial Gaits Video:

Neck Arch and Musculature

A neck with an ideal arch is called an arched neck or turned-over neck. The crest is convex or arched with proportional development of all muscles. The line of the neck flows into that of the back, making for a good appearance and an efficient lever for maneuvering. The strength of the neck with proportional development of all muscles improves the swing of shoulder, elevates the shoulder and body, and aids the horse in engaging its hindquarters through activation of the back. An arched neck is desirable in a horse for any sport.

A ewe neck or upside-down neck bends upward instead of down in the normal arch. This fault is common and seen in any breed, especially in long-necked horses but mainly in the Arabian Horse and Thoroughbred. The fault may be caused by a horse who holds his neck high (stargazing). Stargazing makes it difficult for a rider to control the horse, who then braces on the bit and is hard-mouthed. A ewe neck is counter-productive to collection and proper transitions, as the horse only elevates its head and doesn't engage its hind end. The horse's loins and back may become sore. The sunken crest often fills if the horse is ridden correctly into its bridle. However, the horse's performance will be limited until proper muscling is developed.

A swan neck is set at a high upward angle, with the upper curve arched, yet a dip remains in front of the withers and the muscles bulge on the underside. This is common, especially in Saddlebreds, Gaited horses, and Thoroughbreds. A swan neck makes it easy for a horse to lean on the bit and curl behind without lifting its back. It is often caused by incorrect work or false collection.

A knife neck is a long, skinny neck with poor muscular development on both the top and bottom. It has the appearance of a straight crest without much substance below. A knife neck is relatively common in older horses of any breed. It is sometimes seen in young, green horses. It is usually associated with poor development of back, neck, abdominal and haunch muscles, allowing a horse to go in a strung-out frame with no collection and on its forehand. It is often rider-induced, and usually indicates lack of athletic ability. Knife neck can be improved through skillful riding and the careful use of side reins to develop more muscle and stability. A knife necked horse is best used for light pleasure riding until its strength is developed.

Crest

Large crests are relatively uncommon but can be found in any breed. It is most often seen in stallions, ponies, and draft breeds. There may be a link to the animal being an easy keeper. An excessively large crest puts more weight on the forehand. A large crest is usually caused by large fat deposits above the nuchal ligament. An excessive crest due to obesity or insulin resistance can be treated with a reduced diet. ..." ![]() Equine Conformation

Equine Conformation ![]()

Possible Causes of Some Neck Problems

- Goes from head, travels along the neck, withers, back, loin, croup and ends in the tail.

- Vertebrae can vary from 51 to 57.

- Average vertebrae is 54.

- Neck vertebrae 7 (C1 to C7); dorsal or thoracic (designated T plus a number) vertebrae 18; lumbar (L plus a number) or loin vertebrae 6; sacral or croup vertebrae 5; coccygeal or tail vertebrae 18.

- Spinal cord compression. This can be congenital or due to injury; i.e., spine malformations, injuries that break or reshape the bone, degenerative joint disease, or a combination of these.

- Peripheral nerve compression. This can be congenital or due to injury; i.e., spine malformations, injuries that break or reshape the bone, degenerative joint disease, or a combination of these.

- Cervical joint arthritis

- Narrowing of the spinal canal

- Tumors

Ataxia, or a lack of coordination in gaits, is one of the resulting symptoms. Other neurological signs affecting muscle strength, skin sensation, and body awareness usually accompany ataxia. Sometimes horses perform poorly or have lameness as a result of neuromuscular dysfunction originating in the neck. Referred pain and paresthesia (numbness) aka peripheral nerve signs could be the cause. They are more difficult to detect. A forelimb could be affected by referred pain originating in the neck. Neuromuscular dysfunction is difficult to track.

- Localized muscle soreness could be caused by an asymmetrical rider, poor equipment fit, a fall, or pulling against restraints

- Osteoarthritis of the small articular joints in the neck (facet joints)

- Cervical vertebrae fracture

- Tumors of the vertebrae, muscles, or ligaments

- Cystlike lesions in the cervical vertebrae

- Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative bacteria of Lyme disease

- Nerve root injury associated with first rib trauma or abnormalities

- Neuromuscular dysfunction originating in the neck

- Fractures in vertebrae

- Diseases such as EPM or Lyme Disease

- Parasites such as Neck Threadworms aka(Onchocera) or (Microfilariae)

- Trauma to the soft and/or bony tissue of the neck or poll [For example: Fistulous Withers or Poll Evil]

- Inflammatory disease such as lymph node or muscle abscessation, muscle damage, spinal nerve impingement, or damage to the jugular vein

- Degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis of the cervical facet joints or rarely, disc disease between the neck vertebrae

- Tumors of the neck are rare

- Equine herpesvirus

- West Nile virus

- Wobbler Syndrome (Cervical vertebral compressive myelopathy)

- Vertebral trauma

- Liver failure

- Tumors of the nervous system

- Equine degenerative myelopathy

- Parasites such as Neck Threadworms aka(Onchocera) or (Microfilariae)

With this long list of potential causes and the complicated signs of neck conditions, it is essential that owners and their veterinarians always consider neck problems when confronting poor performance, gait changes and lameness, weakness, and abnormal head carriage and neck positions. Neck related conditions appear to be more common than ever. They are being diagnosed in animals of all ages. Warmblood breeds seem particularly susceptible. Although horses' necks are heavily muscled structures that protect big, sturdy vertebrae and more fragile structures lying beneath, disease and trauma can still occur. Horse owners must watch for signs of neck issues and have a veterinarian evaluate a horse that displays stiffness, soreness, or ataxia. While some neck issues can have lasting consequences, many can be resolved through veterinary management in conjunction with proper physical therapy and adjusted training techniques.

For More Information:

Neck Problems in the HorseThe Horse Curator

Diagnosing Equine Neck Conditions

Developmental Orthopedic Disease (DOD) in Horses, Osteochondrosis (OC), Osteochondritis Dessicans (OCD), Subchondral Bone Cysts (SBC)

Spinal Cord Compression in Horses (CVCM)

Developmental Orthopedic Disease (DOD) in Horses, Osteochondrosis (OC), Osteochondritis Dessicans (OCD), Subchondral Bone Cysts (SBC)