| Home Kids/Big Kids Corner | First Posted: Aug 30, 2010 Jan 21, 2020 | |

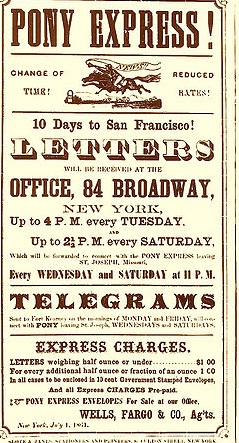

W Pony Express     William H. Russell, William B. Waddell and Alexander Majors Left to Right "The Pony Express was founded by William H. Russell, William B. Waddell, and Alexander Majors. Plans for the Pony Express were spurred by the threat of the Civil War and the need for faster communication with the West. The Pony Express consisted of relays of men riding horses carrying saddlebags of mail across a 2000-mile trail. The service opened officially on April 3, 1860, when riders left simultaneously from St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California. The first westbound trip was made in 9 days and 23 hours and the eastbound journey in 11 days and 12 hours. The pony riders covered 250 miles in a 24-hour day. Eventually, the Pony Express had more than 100 stations, 80 riders, and between 400 and 500 horses. The express route was extremely hazardous, but only one mail delivery was ever lost. The service lasted only 19 months until October 24, 1861, when the completion of the Pacific Telegraph line ended the need for its existence. Although California relied upon news from the Pony Express during the early days of the Civil War, the horse line was never a financial success, leading its founders to bankruptcy. However, the romantic drama surrounding the Pony Express has made it a part of the legend of the American West." OperationA total of about 157 Pony Express stations were placed at intervals of about 10 miles (16 km) along the approximately 2,000 miles (3,200 km) route. This was roughly the maximum distance a horse could travel quickly, either at a trot, a canter or a gallop, depending on the need. The rider changed to a fresh horse at each station, taking only the mail pouch called a mochila (from the Spanish for pouch or backpack) with him. The employers stressed the importance of the pouch. They often said that, if it came to be, the horse and rider should perish before the mochila did. The mochila was thrown over the saddle and held in place by the weight of the rider sitting on it. Each corner had a cantina, or pocket. Bundles of mail were placed in these cantinas, which were padlocked for safety. The mochila could hold 20 pounds (10 kg) of mail along with the 20 pounds of material carried on the horse. Included in that 20 pounds were a water sack, a Bible, a horn for alerting the relay station master to prepare the next horse, a revolver, and a choice of a rifle or another revolver. Eventually, everything except one revolver and a water sack was removed, allowing for a total of 165 pounds (75 kg) on the horse's back. Riders, who could not weigh over 125 pounds, changed about every 75-100 miles (120-160 km), and rode day and night. In emergencies, a given rider might ride two stages back to back, over 20 hours on a quickly moving horse. It is unknown if riders tried crossing the Sierra Nevada in winter, but they certainly crossed central Nevada. By 1860 there was a telegraph station in Carson City, Nevada. The riders received $25 per week as pay. A comparable wage for unskilled labor at the time was about $1 per week. Alexander Majors, one of the founders of the Pony Express, had acquired more than 400 horses for the project. These averaged about 14 1/2 hands (1.47 m) high and averaged 900 pounds (410 kg)[9] each; thus, the name pony was appropriate, even if not strictly correct in all cases. The roughly 1900 mile route roughly followed the Oregon Trail, and California Trail to Fort Bridger in Wyoming and then the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City, Utah. From there it roughly followed the Central Nevada Route to Carson City, Nevada before passing over the Sierras into Sacramento, California. The route started at St. Joseph, Missouri on the Missouri River, it then followed what is modern day US 36-the Pony Express Highway-to Marysville, Kansas, where it turned northwest following Little Blue River to Fort Kearny in Nebraska. Through Nebraska it followed the Great Platte River Road, cutting through Gothenburg, Nebraska and passing Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff, clipping the edge of Colorado at Julesburg, Colorado, before arriving at Fort Laramie in Wyoming. From there it followed the Sweetwater River, passing Independence Rock, Devil's Gate, and Split Rock, to Fort Caspar, through South Pass to Fort Bridger and then down to Salt Lake City. From Salt Lake City it generally followed the Central Nevada Route blazed by Captain James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1859. This route roughly follows today's U.S. Highway 50 across Nevada and Utah. It crossed the Great Basin, the Utah-Nevada Desert, and the Sierra Nevada near Lake Tahoe before arriving in Sacramento. Mail was then sent via steamer down the Sacramento River to San Francisco. On a few instances when the steamer was missed, riders took the mail via horseback to Oakland, California. Indian Attacks on Pony ExpressNotation on cover reads "recovered from a mail stolen by the Indians in 1860" and bears a New York backstamp of May 3, 1862, the date when it was finally delivered in New York. Cover is also franked with U.S. Postage issue of 1857, Washington, 10c black. The Paiute War was a minor series of raids and ambushes initiated by the Paiute Indian tribe in Nevada and which resulted in the disruption of mail services of the Pony Express. It took place from May through June 1860, though sporadic violence continued for a period afterward. In the brief history that the Pony Express operated only once did the mail not go through. After completing eight weekly trips from both Sacramento and Saint Joseph, the Pony Express was forced to suspend mail services because of the outbreak of the Paiute Indian War in May 1860. Approximately 6,000 Paiutes in Nevada had suffered during a winter of fierce blizzards that year. By spring, the whole tribe was ready to embark on a war, except for the Paiute chief named Numaga. For three days Numaga fasted and argued for peace. However, on May 7 a few Indians raided the Williams Pony Express Station anyway, killing five men. During the following weeks, other isolated incidents occurred when whites in Paiute country were ambushed and killed. The Pony Express was a special target. Seven other express stations were also attacked; some 16 employees were killed and approximately 150 express horses were either stolen or driven off. The Paiute war cost the Pony Express company about $75,000 in livestock and station equipment, not to mention the loss of life. In June of that year, the Paiute uprising had been ended through the intervention of U.S. government troops, after which four delayed mail shipments from the East were finally brought to San Francisco on June 25, 1860. During this brief war, one Pony Express mailing, which left San Francisco on July 21, 1860 did not immediately reach its destination; the mail pouch (Mochila) did not arrive in St. Joseph and then on to New York until almost two years later. Famous Riders

Back in 1860, riding for the Pony Express was difficult work - riders had to be tough and lightweight. There is a famous advertisement that reportedly read, "Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred." The Pony Express had an estimated 80 riders that were in use at any one given time. In addition, there were also about 400 other employees including station keepers, stock tenders and route superintendents. Many young men applied for jobs with the Pony Express, all eager to face the dangers and the challenges that sometimes lay along the delivery route. Famous American author Mark Twain, who saw the Pony Express in action first hand, described the riders as: "...usually a little bit of a man." Though the riders were small, lightweight, generally teenage boys, their untarnished record proved them to be heroes of the American West for the much needed and dangerous service they provided for the nation. A list of riders has been compiled by the staff of the St. Joseph Museum from various sources, including accounts from people who knew riders, relatives of riders and newspapers. Some of the riders' names are listed in reference. (See Wikipedia Article-follow link above) First Riders

The first westbound rider to depart St. Joseph has been disputed but at this late date most historians have boiled it down to either Johnny Fry or Billy Richardson also known as Johnson William Richardson. Both Expressmen were hired at St. Joseph for A. E. Lewis' Division which ran from St. Joseph to Seneca, Kansas, a distance of eighty miles. They covered at an average speed of twelve and a half miles per hour, including all stops. Before the mail pouch was delivered to the first rider, time was taken out for ceremonies and several speeches. First, Mayor M. Jeff Thompson gave a brief speech on the significance of the event for St. Joseph. Then William H. Russell and Alexander Majors addressed the gala crowd about how the Pony Express was just a "precursor" to the construction of a transcontinental railroad. At the conclusion of all the speeches, approximately 7:15 p.m., Russell turned the mail pouch over to the first rider. A cannon fired, the large assembled crowd cheered, and the rider dashed to the landing at the "foot of Jules Street where the ferry boat Denver, alerted by the signal cannon, waited to carry the horse and rider across the Missouri River to Elwood, Kansas Territory." On April 9 at 6:45 p.m., the first rider from the east reached Salt Lake City, Utah. Then, on April 12, the mail pouch reached Carson City, Nevada at 2:30 p.m. The riders raced over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, through Placerville, California and on to Sacramento. Around midnight on April 14, 1860, the first mail pouch was delivered via the Pony Express to San Francisco. James Randall is credited as the first eastbound rider from the San Francisco Alta telegraph office since he was on the steamship Antelope to go to Sacramento. Mail for the Pony Express left San Francisco at 4:00 pm, carried by horse and rider to the waterfront, and then on by steamboat to Sacramento where it was picked up by the Pony Express rider. At 2:45 a.m., William (Sam) Hamilton was the first Pony Express rider to begin the journey from Sacramento. He rode all the way to Sportsman Hall Station where he gave his mochila filled with mail to Warren Upson. A California Registered Historical Landmark's plaque at the site reads: This was the site of Sportsman's Hall, also known as the Twelve-Mile House. The hotel operated in the late 1850s and 1860s by John and James Blair. A stopping place for stages and teams of the Comstock, it became a relay station of the central overland Pony Express. Here, at 7:40 a.m., April 4, 1860, Pony rider William (Sam) Hamilton, riding in from Placerville, handed the Express mail to Warren Upson who, two minutes later, sped on his way eastward. William Cody

Probably more than any other rider in the Pony Express, William Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill epitomizes the legend and the folk lore of the Pony Express. Numerous stories have been told of young Cody's adventures as a Pony Express rider. When Cody was only 15 years old he was employed as a rider and was given a short 45-mile delivery run from the township of Julesburg which lay to the west. After some months he was transferred to Slade's Division in Wyoming where he made the longest non-stop ride from Red Buttes Station to Rocky Ridge Station and back when he found that his relief rider had been killed. The distance of 322 miles over one of the most dangerous sections of the entire trail was completed in 21 hours and 40 minutes. It took a total of 21 horses to complete this run. Cody was present for every significant chapter in young western history, including the gold rush, the building of the railroads, and cattle herding on the Great Plains-and found himself playing a part in nearly every one of these crucial stages of development. A career as a scout during the Civil War earned him his nickname and established his notoriety as a model frontiersman. Robert Haslam

"Pony Bob" Haslam was among the most brave, resourceful, and best known riders of the Pony Express. He was born January 1840 in London, England, and came to U.S. as a teen. Haslam was hired by Bolivar Roberts, helped build the stations, and was given the mail run from Friday's Station at Lake Tahoe to Buckland's Station near Fort Churchill which was 75 miles to the east. Perhaps his greatest ride, 120 miles in 8 hours and 20 minutes while wounded, was an important contribution to the fastest trip ever made by the Pony Express. The message carried Lincoln's inaugural address. Pony Bob Haslam's ride was the result of the Indian problems in 1860. He had received the eastbound mail (probably the May 10 mail from San Francisco) at Friday's Station. At Buckland's Station his relief rider was so badly frightened over the Indian threat that he refused to take the mail. Haslam agreed to take the mail all the way to Smith's Creek for a total distance of 190 miles without a rest. After a rest of nine hours, he retraced his route with the westbound mail. At Cold Springs he found that Indians had raided the place, killing the station keeper and running off all of the stock. Finally he reached Buckland's Station, making the 380-mile round trip the longest on record. On the ride he was shot through the jaw with an Indian arrow, losing three teeth. Jack Keetley

Jack Keetley was hired by A. E. Lewis for his Division at the age of nineteen, and put on the run from Marysville to Big Sandy. He was one of those who rode for the Pony Express during the entire nineteen months of its existence. Jack Keetley's longest ride, upon which he doubled back for another rider, ended at Seneca where he was taken from the saddle sound asleep. He had ridden 340 miles in thirty-one hours without stopping to rest or eat. After the Pony Express was disbanded, Keetley went to Salt Lake City where he engaged in mining. HorsesAn estimated 400 horses in total were used by the Pony Express to deliver the mail. Horses were selected for swiftness and endurance. On the east end of Pony Express route the horses were usually selected from US Calvary units. At the west end of the pony Express route in California, W.W. Finney purchased 100 head of short coupled stock called "California Horses" while A.B. Miller purchased another 200 native ponies in and around the Great Salt Lake Valley. The horses were ridden quickly between stations, an average of 15 miles, and then were relieved and a fresh horse would be exchanged for the one that just arrived from its strenuous run. During his route of 80 to 100 miles, a Pony Express rider would change horses 8 to 10 times. The horses were ridden at a fast trot, canter or gallop, around 10 to 15 miles per hour and at times they were driven to full gallop at speeds up to 25 miles per hour. Horses of the Pony Express were purchased in Missouri, Iowa, California, and some western U.S. territories. The various types of horses ridden by riders of the Pony Express included Morgans and Thoroughbreds which were often used on the eastern end of the trail. Pintos were often used in the middle section and Mustangs were often used on the western (more rugged) end of the mail route.

In 1844 years before the Pony Express came to St. Joseph, Israel Landis opened a small saddle and harness shop there. His business expanded as the town grew, and when the Pony Express came to town Landis was the ideal candidate to produce saddles for the new found Pony Express. Because Pony Express riders rode their horses at quickly over a distance of ten and more miles between stations, every consideration was made to reduce the overall weight the horse had to carry. To help reduce this load, special light weight saddles were designed and crafted. Using less leather and fewer metallic and wood components they fashioned a saddle that was similar in design to the regular stock saddle generally in use in the West at that time. The mail pouch was a separate component to the saddle that made the Pony Express unique. Standard mail pouches for horses were never employed because of their size and shape, as it was time consuming detaching and attaching it from one saddle to the other, causing undue delay in changing mounts. With many stops to make, the delayed time at each station would accumulate to appreciable proportions. To get around this difficulty, a Mochila, or covering of leather, was thrown over the saddle. The saddle horn and cantle projected through holes which were specially cut to size in the mochila. Attached to the broad leather skirt of the mochila were four cantinas, or box-shaped hard leather compartments were letters were carried on the journey. ClosingAlthough the Pony Express proved that the central/northern mail route was viable, Russell, Majors and Waddell did not get the contract to deliver mail over the route. The contract was instead awarded to Jeremy Dehut in March 1861, who had taken over the southern Congressionally favored Butterfield Overland Mail Stage Line. Holladay took over the Russell, Majors and Waddell stations for his stagecoaches. Shortly after the contract was awarded, the start of the American Civil War caused the stage line to cease operation. From March 1861, the Pony Express ran mail only between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. The Pony Express announced its closure on October 26, 1861, two days after the transcontinental telegraph reached Salt Lake City and connected Omaha, Nebraska and Sacramento, California. Other telegraph lines connected points along the line and other cities on the east and west coasts. The Pony Express had grossed $90,000 and lost $200,000. In 1866, after the American Civil War was over, Holladay sold the Pony Express assets along with the remnants of the Butterfield Stage to Wells Fargo for $1.5 million. Legacy

Wells Fargo used the Pony Express logo for its guard and armored car service. The logo continued to be used when other companies took over the security business into the 1990s. Effective 2001, the Pony Express logo was no longer used for security businesses since the business has been sold. In June 2006, the United States Postal Service announced it had trademarked "Pony Express" along with Air Mail. "Pony Express" is a trademarked name used by Freight Link international courier services company in Russia; their logo is similar to the one trademarked by United States Postal Service with "Since 1860" written under the image. Its route has been designated the Pony Express National Historic Trail. Approximately 120 historic sites along the trail may eventually be open to the public, including 50 stations or station ruins. About the MuseumAn historic structure which was a portion of the Pikes Peak Stables in St. Joseph, MO was preserved and turned into the National Pony Express Museum. Through the help and efforts of the Chamber of Commerce, the citizens of St. Joseph, and M. Kaerl Goetz and the Goetz Pony Express Foundation, the structure was saved. When finished it was opened to the public as the Pony Express Museum. The original renovations took place in the 1950s. Later in 1992, further restoration continued. The stable was renovated to its original size. The museum depicts the genesis and life of the Pony Express Mail Service which lasted began in April 1860 to October 1861. Today it preserves the legend and legacy of this special time in our history. For More Information: Compilation of People, Places, Vocabulary, and Dates of the Pony Express |